Better & worse forms of economic "stimulus"

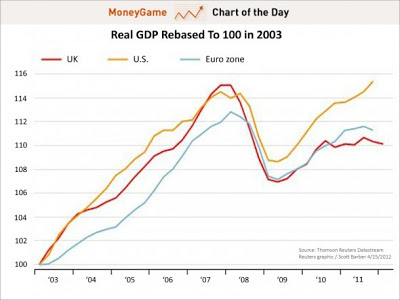

(From Business Insider, April 2012. This graph updated an October 2011 US/UK comparison, here, which already showed the US economic recovery pulling ahead significantly, despite unremitting Republican sabotage and obstructionism. The contrasts are even stronger now ... as shown by the graph at the end of this post.)

------------------------------

First, let's review the basics. As I've noted before (please pardon the repetition):

In some ways, admittedly, the idea that governments should respond to economic downturns with policies of fiscal "austerity"—that is, with spending cuts and other measures to reduce their growing deficits—may seem like common sense. To quote one popular but misleading slogan, when individuals and families have to tighten their belts, government should tighten its belt too. And before the 1930s, this piece of economic folklore would also have been regarded as sound and responsible mainstream economics.It is now almost five years since the beginning of the financial crisis in 2008, which triggered the big economic crash of 2008-2009 from which we are still struggling to recover. Different economic policies have been followed in different countries—more Keynesian in the US, despite unrelenting Republican sabotage and obstructionism, though not Keynesian enough ... and more anti-Keynesian in Europe, most notably in Britain.

Unfortunately, life is sometimes more complicated than that. Ever since the Great Depression of the 1930s and the work of John Maynard Keynes it has been recognized—or, at least, it should be generally recognized—that this is precisely the wrong way to respond to an economic crash. In that kind of situation, a fixation on government deficit-cutting is not just misplaced and harmful but systematically counterproductive and self-defeating. As the amount of demand in the overall economy slumps, withdrawing further demand from the economy through those "austerity" policies just accelerates a self-reinforcing contractionary spiral. Insufficient demand reduces sales and discourages investment, businesses cut back or go bust, unemployment increases and incomes shrink, consumers have less money to spend, and so on ... with the result that the economy declines even further or, at best, remains stuck at a depressed level where it is operating well below capacity. A shrinking economy also yields smaller government revenues from taxes, increasing government deficits, and for governments to try to improve that situation with spending cuts and/or tax increases will reinforce contractionary tendencies in the economy. In the meantime, there is a lot of unnecessary suffering and social disruption.

Some key implications are pretty clear. To put it bluntly, when the economy is threatened by or recovering from a major recession, the government should be running a deficit (except in exceptional situations that make this difficult or dangerous) to pump more demand into the system, offset contractionary dynamics, and help promote economic recovery. In the US case, for various reasons, the major responsibility for doing this rests with the federal government, not state and local governments. (And, by the way, if you've been hoodwinked by right-wing propaganda into believing that the Obama administration's 2009 economic "stimulus" didn't work, thus disproving Keynes on this point, think again.) More generally, fiscal policy should be counter-cyclical. Everything else being equal, governments should bring down their deficits in good times, not bad times. The time for governments to balance the budget, run surpluses, or pay down the debt is when the economy is booming. During downswings in the business cycle, let alone major economic crises, trying to do those things is a bad idea.

All of that is a fairly straightforward recapitulation of what should be conventional economic wisdom, and before the 2008 crash I would have guessed that these basic (I mean really basic) Keynesian insights were generally accepted, at least by informed analysts and policymakers. But the experience of the past four years has made it clear that many people find the points I've just outlined controversial, deeply counter-intuitive, or even surprising. Whether those views stem from economic illiteracy, partisan demagoguery, or a quasi-theological commitment to pre-Keynesian economic dogmas, they have unfortunately been pervasive and influential—and very damaging, since they happen to be quite misguided. [....]

Well, the results are in – Keynes was right, contractionary economics was wrong, but the damage is done. If you want a quick comparison of life with and without economic "stimulus", just check the graph at the beginning of this post. As you examine that graph, bear in mind that the kinds of policies favored by the Republicans and the right-wing propaganda apparatus (including, for example, the Wall Street Journal editorial page) generate the red and blue lines, as opposed to the yellow line.

With respect to the continued sluggishness of the economic recovery in the US, part of the blame lies with the excessive timidity and caution of the Obama administration and the Congressional Democrats in 2009, when there was still a filibuster-proof Democratic majority in the Senate (though the 2009 economic "stimulus" did, at least, help keep the economy from going over the edge into another Great Depression). But fundamentally, in this context as in so many others, the Republicans are the problem—not the only problem, admittedly, but a crucial and dangerous problem—and any discussions of economic policy, unemployment, and the slow pace of recovery from the Great Recession that try to evade or obscure this central reality are not worth taking seriously.

In practice, of course, ever since around 1980 the Republicans have shown that they accept the idea of using fiscal "stimulus" to respond to economic downturns—as long as that stimulus takes the form of cutting taxes, especially for the wealthiest taxpayers. More precisely, whenever Republican presidents are in office, Congressional Republicans tend to vote according to the principle, enunciated so crisply by Dick Cheney, that "Reagan proved deficits don't matter". Then, when Democratic presidents are in office, they temporarily start hyper-ventilating about the federal deficit again—while also refusing to raise taxes on the rich as part of reducing the deficit. But be that as it may ...

=> Once one faces the fact that counter-cyclical fiscal policies are a necessary part of responding to severe economic slumps, in order to pump needed "stimulus" into the economy, one then has to consider what kinds of economic stimulus are most effective in promoting economic recovery and reducing unemployment.

As Jonathan Chait recently reminded us, back in 2010 Dylan Matthews took the trouble to lay out some relevant comparisons, based on various estimates by solidly mainstream economic analysts.

The pattern is striking: Direct government spending -- through unemployment benefits, food stamps, work sharing or infrastructure spending -- top the list, giving you more than a dollar's worth of stimulus for a dollar's worth of spending, while cuts to taxes affecting businesses and upper-income individuals -- such as the corporate, dividend, capital gains and alternative minimum taxes -- give you less.As one might expect, the forms of economic "stimulus" most favored by Republicans, then and since, are among the least effective in terms of promoting economic recovery and reducing unemployment—though, to be fair, they are among the most effective in terms of increasing after-tax income for the wealthy and helping increase overall economic inequality. On the other hand, the forms of stimulus most effective in terms of promoting economic recovery and reducing unemployment (look down toward the bottom of the chart below) have been fought tooth-and-nail by the Republicans.

The reason there is clear: A tax cut that ends up with upper-income folks gets saved rather than spent, and a dollar saved doesn't stimulate the economy. That's why some tax breaks, such as the job tax credit and payroll tax holiday, are fairly effective, though still less so than direct spending. The problem, of course, is that the politics of tax breaks are easier than the politics of spending, even though the tax breaks are actually more expensive. But if the government wants the maximum stimulus at the minimum deficit cost, direct spending is the way to go.

What conclusions should one draw? We report, you decide.

—Jeff Weintraub

P.S. By the way, "increased infrastructure spending" to start rebuilding, repairing, updating, and otherwise strengthening our national infrastructure would not only employ a lot of people and help stimulate economic recovery, but would also make excellent sense in terms of long-term public investment. Even Peggy Noonan can see that—though she doesn't seem to have noticed that her party has relentlessly blocked this, too.

===================================

Washington Post Online (Wonkblog)

June 17, 2010

Research desk: What's a dollar of stimulus worth?

By Dylan Matthews

BHeffernan1 asks:

How many jobs does a federal gov dollar buy? Provide optimistic (most efficient -- extending unemployment? building a smart power grid?), median and pessimistic (tax cuts for wealthy?).For reasons Ezra has laid out in the past, it's best to focus not on job creation narrowly, but on the general economic impact of a policy. Policies that create jobs have other benefits (and costs) as well. If you're evaluating a proposal to pay workers to build a railroad, you want to know what the value of that railroad is, not just how many workers were hired. If you're giving laid-off workers unemployment insurance, the point isn't just job creation, but also helping them pay rent. So if you want raw job estimates for different policies, see Moody's analysis of the cost per job of job tax credit proposals, or CAP's look (PDF) at the job creation potential of various clean-energy investments. But keep in mind they leave out important effects of various proposals.

We can get a better picture of the overall effectiveness of a stimulus method by looking at its contribution to GDP. The most recent numbers come from April's Senate testimony (PDF) from Mark Zandi of Moody's. Zandi calculated the change in GDP caused by a dollar spent on various stimulus policies. Here are the results, grouped from least effective to most effective. You might want to click [here] to see the larger, and more readable, version.

The pattern is striking: Direct government spending -- through unemployment benefits, food stamps, work sharing or infrastructure spending -- top the list, giving you more than a dollar's worth of stimulus for a dollar's worth of spending, while cuts to taxes affecting businesses and upper-income individuals -- such as the corporate, dividend, capital gains and alternative minimum taxes -- give you less.

The reason there is clear: A tax cut that ends up with upper-income folks gets saved rather than spent, and a dollar saved doesn't stimulate the economy. That's why some tax breaks, such as the job tax credit and payroll tax holiday, are fairly effective, though still less so than direct spending. The problem, of course, is that the politics of tax breaks are easier than the politics of spending, even though the tax breaks are actually more expensive. But if the government wants the maximum stimulus at the minimum deficit cost, direct spending is the way to go.

<< Home