(From

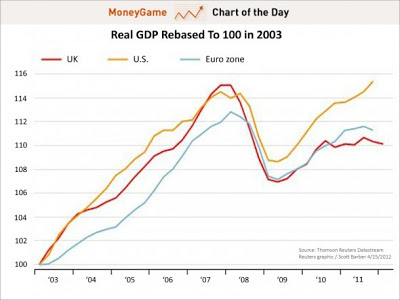

Business Insider, April 2012. This graph updates an October 2011 US/UK comparison,

here, which already showed the US economic recovery pulling ahead significantly, despite unremitting Republican sabotage and obstructionism. The contrasts would be even stronger now, in December 2012.)

--------------------

In some ways, admittedly, the idea that governments should respond to economic downturns with policies of fiscal "austerity"—that is, with spending cuts and other measures to reduce their growing deficits—may seem like common sense. To quote one popular but misleading slogan, when individuals and families have to tighten their belts, government should tighten its belt too. And before the 1930s, this piece of economic folklore would also have been regarded as sound and responsible mainstream economics.

Unfortunately, life is sometimes more complicated than that. Ever since the Great Depression of the 1930s and the work of John Maynard Keynes it has been recognized—or, at least, it

should be generally recognized—that this is precisely the

wrong way to respond to an economic crash. In that kind of situation, a fixation on government deficit-cutting is not just misplaced and harmful but systematically counterproductive and self-defeating. As the amount of demand in the overall economy slumps, withdrawing further demand from the economy through those "austerity" policies just accelerates a self-reinforcing contractionary spiral. Insufficient demand reduces sales and discourages investment, businesses cut back or go bust, unemployment increases and incomes shrink, consumers have less money to spend, and so on ... with the result that the economy declines even further or, at best, remains stuck at a depressed level where it is operating well below capacity. A shrinking economy also yields smaller government revenues from taxes, increasing government deficits, and for governments to try to improve that situation with spending cuts and/or tax increases will reinforce contractionary tendencies in the economy. In the meantime, there is a lot of unnecessary suffering and social disruption.

Some key implications are pretty clear. To put it bluntly, when the economy is threatened by or recovering from a major recession, the government

should be running a deficit (except in exceptional situations that make this difficult or dangerous) to pump more demand into the system, offset contractionary dynamics, and help promote economic recovery. In the US case, for various reasons, the major responsibility for doing this rests with the federal government, not state and local governments. (And, by the way, if you've been hoodwinked by right-wing propaganda into believing that the Obama administration's 2009 economic "stimulus" didn't work, thus disproving Keynes on this point,

think again.) More generally, fiscal policy should be

counter-cyclical. Everything else being equal, governments should bring down their deficits in good times, not bad times. The time for governments to balance the budget, run surpluses, or pay down the debt is when the economy is booming. During downswings in the business cycle, let alone major economic crises, trying to do those things is a

bad idea.

All of that is a fairly straightforward recapitulation of what should be conventional economic wisdom, and before the 2008 crash I would have guessed that these basic (I mean

really basic) Keynesian insights were generally accepted, at least by informed analysts and policymakers. But the experience of the past four years has made it clear that many people find the points I've just outlined controversial, deeply counter-intuitive, or even surprising. Whether those views stem from economic illiteracy, partisan demagoguery, or a quasi-theological commitment to pre-Keynesian economic dogmas, they have unfortunately been pervasive and influential—and very damaging, since they happen to be quite misguided.

=> As a number of analysts have pointed out over the past several years, we have a first-rate natural experiment available to help confirm that diagnosis. In American economic debates and demagoguery, there has been a lot of talk about the dangers of the US turning into Greece. But in many ways that's wildly misleading, since Greece is a very different sort of country from the US, with very different economic circumstances. The more logical and informative comparisons would be with the larger & stronger western European economies ...

... and especially with Britain, where the Conservative-led government elected in May 2010 decided to pursue Republican-style austerity policies in a serious and consistent way. (If you check out the graph above, May 2010 is the point when the red line, for the British economy, stops rising and goes flat. That's not a coincidence.) In the US, on the other hand, the Obama administration has responded to the Great Recession with broadly Keynesian policies of economic stimulus and counter-cyclical deficit spending—despite unrelenting Republican sabotage and obstructionism, combined with

excessive timidity and unwise concessions to deficit hysteria on the Democratic side. They could have done it better, and they should have done it more aggressively, but basically they've done it.

With what results? As John Cassidy explains in a very nice recent piece, the lesson to be learned from this concrete comparison is very clear: "

It’s Official: Austerity Economics Doesn’t Work". Some highlights:

[....] In making his annual Autumn Statement to the House of Commons on Wednesday, George Osborne, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was forced to admit that his government has failed to meet a series of targets it set for itself back in June of 2010, when it slashed the budgets of various government departments by up to thirty per cent. Back then, Osborne said that his austerity policies would cut his country’s budget deficit to

zero within four years, enable Britain to begin relieving itself of its public debt, and generate healthy economic growth. None of these things have happened. Britain’s deficit remains stubbornly high, its people have been suffering through a double-dip recession, and many observers now expect the country to lose its “AAA” credit rating.

One of the frustrations of economics is that it is hard to carry out scientific experiments and prove things beyond reasonable doubt. But not in this case. Thanks to Osborne’s stubborn refusal to change course—“Turning back would be a disaster,” he told Parliament—what has been happening in Britain amounts to a “natural experiment” to test the efficacy of austerity economics. For the sixty-odd million inhabitants of the U.K., living through it hasn’t been a pleasant experience—no university institutional-review board would have allowed this kind of brutal human experimentation. But from a historical and scientific perspective, it is an invaluable case study.

At every stage of the experiment, critics (myself included) have warned that Osborne’s austerity policies would prove

self-defeating. [JW: And that's not just hindsight. For one roundup of some of those warnings in 2010, see here.] [....] Osborne, relying on arguments about restoring the confidence of investors and businessmen that his forebears at the U.K. Treasury used during the early nineteen-thirties against Keynes, insisted (and continues to insist) otherwise, but he has been proven wrong.

With Republicans in Congress still intent on pursuing a strategy similar to

the failed one adopted by the Brits, this is a story that needs trumpeting. Austerity policies are self-defeating: they cripple growth and reduce tax revenues. The only way to bring down the U.S. government’s deficit in a sustainable manner, and put the nation’s finances on a firmer footing, is to keep the economy growing. Spending cuts and tax increases can also play a role, but they need to be introduced gradually. [....]

That austerity has led to recession is undeniable. [....] But Osborne was determined to go ahead with his grisly exercise in pre-Keynesian economics. [....]

If all the pain he has inflicted had transformed Britain’s fiscal position, his policies could perhaps be defended. But that hasn’t happened. [....] The debt-to-G.D.P. ratio, which Osborne originally said would peak at about seventy per cent, has now hit seventy-five per cent, and it is forecast to come close to eighty per cent in 2015-2016. It was supposed to start falling next year. Now, it is set to keep climbing until at least 2017-2018.

A comparison with what has happened on this side of the Atlantic is illuminating. For the purposes of the natural experiment, the U.S. can be thought of as the control. In adopting a fiscal stimulus of gradually declining magnitude over the past four years, the Obama Administration has administered what was, until recently, the standard medicine for a sick economy.

As one would have expected on the basis of the textbooks, the American economy, while hardly racing ahead, has fared considerably better than its British counterpart. [....] What may be more surprising—at least to those of you who have been listening to the deficit hawks—is that the United States, while sticking with Keynesian stimulus policies, has also managed to bring down the size of its deficit, relative to G.D.P., almost as rapidly as hairshirt Britain has. [....]

Let’s go over that one more time. Having adopted the policies of Keynes in response to a calamitous recession, the United States has grown more than twice as fast during the past three years as Britain, which adopted the economics of Hoover (and Paul Ryan). Meanwhile, the gaping hole in the two countries’ budgets has declined at roughly the same rate, and next year the U.S. will be in better fiscal shape than its old ally.

Q.E.D.

—Jeff Weintraub

==============================

New Yorker

December 7, 2012

It’s Official: Austerity Economics Doesn’t Work

By

John Cassidy

With all the theatrics going on in Washington, you might well have missed the most important political and economic news of the week: an official confirmation from the United Kingdom that austerity policies don’t work.

In making his annual Autumn Statement to the House of Commons on Wednesday, George Osborne, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was

forced to admit that his government has failed to meet a series of targets it set for

itself back in June of 2010, when it slashed the budgets of various government departments by up to thirty per cent. Back then, Osborne said that his austerity policies would cut his country’s budget deficit to zero within four years, enable Britain to begin relieving itself of its public debt, and generate healthy economic growth. None of these things have happened. Britain’s deficit remains stubbornly high, its people have been suffering through a double-dip recession, and many observers now

expect the country to lose its “AAA” credit rating.

One of the frustrations of economics is that it is hard to carry out scientific experiments and prove things beyond reasonable doubt. But not in this case. Thanks to Osborne’s stubborn refusal to change

course—“Turning back would be a disaster,” he

told Parliament—what has been happening in Britain amounts to a “natural experiment” to test the efficacy of austerity economics. For the sixty-odd million inhabitants of the U.K., living through it hasn’t been a pleasant experience—no university institutional-review board would have allowed this kind of brutal human experimentation. But from a historical and scientific perspective, it is an invaluable case study.

At every stage of the experiment, critics (

myself included) have warned that Osborne’s austerity policies would prove self-defeating. [....] Osborne, relying on arguments about restoring the confidence of investors and businessmen

that his forebears at the U.K. Treasury used during the early nineteen-thirties against Keynes, insisted (and continues to insist) otherwise, but he has been proven wrong.

With Republicans in Congress still intent on pursuing a strategy similar to the failed one adopted by the Brits, this is a story that needs trumpeting. Austerity policies are self-defeating: they cripple growth and reduce tax revenues. The only way to bring down the U.S. government’s deficit in a sustainable manner, and put the nation’s finances on a firmer footing, is to keep the economy growing. Spending

cuts and tax increases can also play a role, but they need to be introduced gradually.

Before the last election there, which took place in May, 2010, the

U.K.’s economy appeared to be slowly recovering from the deep slump of

2008-09 that followed the housing bust and global financial crisis. Just

like the Bush Administration (2008) and the Obama Administration

(2009), Gordon Brown’s Labour government had introduced a fiscal

stimulus to help turn the economy around. G.D.P. was growing at an

annual rate of about 2.5 per cent. Once Osborne’s cuts in spending

started to be felt, however, things changed dramatically. In the fourth

quarter of 2010, growth turned negative and a double-dip recession

began. So far, it has lasted two years. While G.D.P. did expand in the

third quarter of this year, the Office of Budget Responsibility, an

independent economic agency that Osborne set up, has said that it

expects

another decline in the current quarter. For 2013, the O.B.R. is forecasting G.D.P.

growth of just 1.3 per cent. With the economy so weak, the O.B.R. says

that the unemployment rate will tick up from eight per cent to 8.2 per

cent next year.

That austerity has led to recession is undeniable. Despite the Bank of England slashing interest rates and adopting a policy of quantitative easing, consumer and investment spending have remained depressed. Osborne places much of the blame on continental Europe, Britain’s biggest trading partner, but that’s a lame excuse. It was perfectly clear back in 2010 that Europe was headed for trouble. The proper reaction to a negative external shock is to loosen fiscal policy, not tighten it, much less tighten it violently. But Osborne was determined to go ahead with his grisly exercise in pre-Keynesian economics.

If all the pain he has inflicted had transformed Britain’s fiscal position, his policies could perhaps be defended. But that hasn’t happened. Back in 2009, the O.B.R. predicted that by the end of 2013-2014, the deficit would have fallen to 3.5 per cent of G.D.P. Now, the O.B.R. says that the actual figure will be 6.1 per cent. And since most of its forecasts have proved too optimistic, this might well be

another underestimate. Even by Osborne’s preferred measure, which adjusts the headline figure for the state of the economy and doesn’t count capital spending, the deficit won’t be eliminated before 2016-17 at the earliest. The debt-to-G.D.P. ratio, which Osborne originally said would peak at about seventy per cent, has now hit seventy-five per cent, and it is forecast to come close to eighty per cent in 2015-2016. It was supposed to start falling next year. Now, it is set to keep

climbing until at least 2017-2018.

A comparison with what has happened on this side of the Atlantic is illuminating. For the purposes of the natural experiment, the U.S. can be thought of as the control. In adopting a fiscal stimulus of gradually declining magnitude over the past four years, the Obama Administration has administered what was, until recently, the standard medicine for a sick economy.

As one would have expected on the basis of the textbooks, the American economy, while hardly racing ahead, has fared considerably better than its British counterpart. Between 2010 and 2012, G.D.P. growth here has averaged about 2.1 per cent. For the U.K., the figure is 0.9 per cent. What may be more surprising—at least to those of you who have been listening to the deficit hawks—is that the United States, while sticking with Keynesian stimulus policies, has also managed to bring down the size of its deficit, relative to G.D.P., almost as rapidly as hairshirt

Britain has. Back in 2009, at the depths of the recession, both countries had double-digit deficits. Today, the U.S. deficit stands at

about seven per cent of G.D.P., and the British deficit is about five per cent of G.D.P. But with the U.S. growing faster than the U.K,. the gap is set to close. Next year, according to the latest forecasts from the

Congressional Budget Office and the O.B.R., the U.S. deficit will be considerably smaller than the U.K. deficit: four per cent of G.D.P. compared to six per cent.

Let’s go over that one more time. Having adopted the policies of Keynes in response to a calamitous recession, the United States has grown more than twice as fast during the past three years as Britain, which adopted the economics of Hoover (and Paul Ryan). Meanwhile, the gaping hole in the two countries’ budgets has declined at roughly the same rate, and next year the U.S. will be in better fiscal shape than its old ally.

Q.E.D.